I have been struggling for the last few days trying to understand the issues behind packaging and installing the Enthought Tool Suite. I think have been making progress, though only in my head, no actual code or packages so far are terribly satisfying.

The problem

If you are developing a Python-only program, with only dependencies on the standard library, you have no problems with packaging. You can ship tarballs, MSI installer, eggs, … all this works.

However, if you want to develop a rich program that provides many features in a closely integrated and consistent way to the user, you will have to depend on external packages. I know that many projects work around this by including the external dependencies inside the project, or simply reinventing the wheel. Well this does not scale. We cannot expect to develop a major scientific tool and community this way. Reuse is the key to scalability, in my opinion. Thus comes the problem, how to we ship our program?

The problem can be very well seen with the Enthought Tool Suite (ETS). The ETS is a suite of many different packages, all pretty much geared towards building interactive scientific application. In house, Enthought, the company (disclaimer: I do not work for Enthought) uses these packages to develop domain-specific applications for customers. They have broken up the suite in a set of small packages, to enable assembling applications by requiring only the features you need. This is important because if you want to use ETS’s 3D plotting package (TVTK or Mayavi), but you want to stick with MatPlotLib to do 2D plotting, and not use Chaco, you should be able to download only what you need.

As a result the ETS is made of a set of interdependent packages. Maybe they went a bit too far in the modularity, and there are almost 50 packages. The dependency graph looks like this:

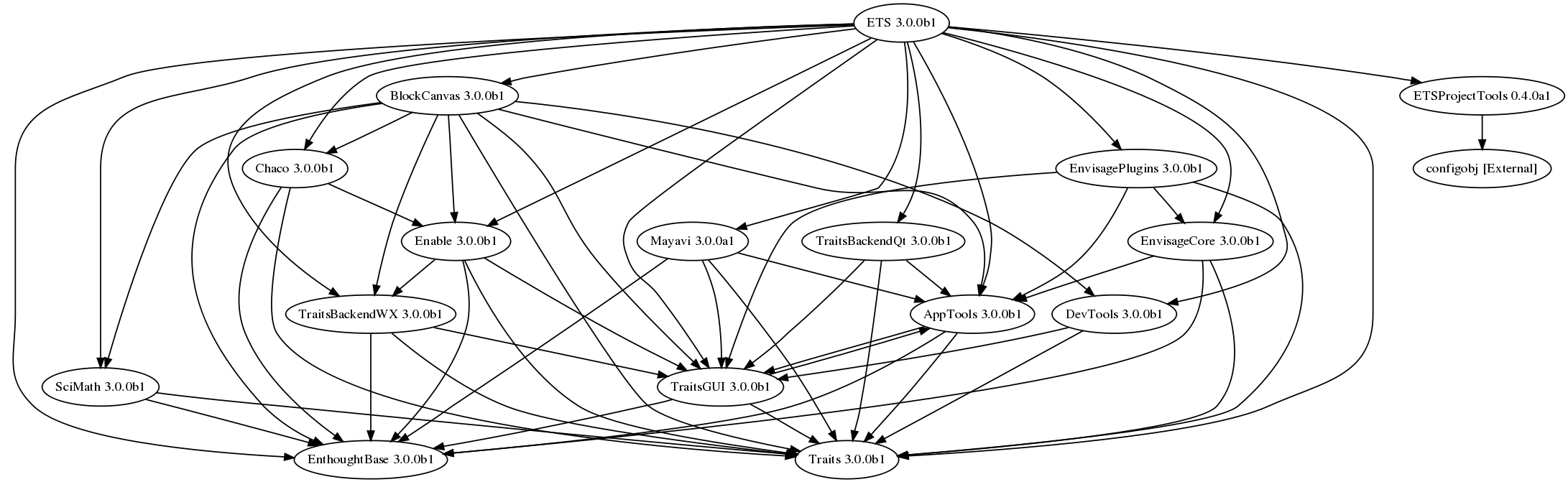

Just to reassure you, the next version of the ETS has a much reduced number of packages, just because some packages where grouped, and the dependency graph indeed is sane:

As you can see, there is a complex dependency graph. So how do you ship this to the user? Another problem that should not be underestimated is: how do you make it easy for people who distribute your projects to package this?

Setuptools

Python has no good answer for this problem, but setuptools do go part of the way. Dependencies in the ETS are declared using setuptools, and installing the ETS strongly relies on setuptools.

Setuptools provides a way of automatically downloading dependencies. However, it is not a full packaging system replacement. The reason I say this is that it does not have the knowledge of a dependency graph, it just downloads packages, introspects them to find their dependencies, and recursively tries to satisfy them by downloading more. Phillip J. Eby (the author of setuptools) has been quite clear that he does not want to write an APT replacement, tough people keep getting it wrong and making the equation “easy_install = apt for Python” (IMHO this is due to bad communication on setuptools webpage).

Moreover, setuptools does not provide an easy to use API to extract all the information it has about packages, dependencies, and download URLs. It is thus not trivial to plug packages shipped with setuptools in an other package manager like rpm or apt. This is why bothers me most, because this is strongly limiting the exposure the ETS is getting in distributions (whether they be Linux distributions, or scientific computing “superpacks”). Recently I have had discussions with somebody on how to ship Mayavi in a monolithic distribution he has developed. He agreed to ship setuptools with the distribution, so now I need to give him a list of eggs to provide. There is no obvious way to get this list using setuptools (insert here big big rant). So I thought that an option was to install Mayavi in a virtual environment to trac the eggs added, and use this information. However, this person’s internet access was possible only by login on dumbed-down servers for security reasons. So we hit a wall. And for me this wall is a wall we keep hitting with setuptools: setuptools does everything for you, the download, the building the install. It does have flags to control these processes, but it does not expose the information you need to do this without using it. I actually think the reason it does not expose this information is that it does not know it a priori. Looking at the code it does seem so. In addition, the structure of the packages make it hard to do.

From packages to repositories

On the other side, Dave Peterson, at Enthought, has been working on a tool to allow checking out of the ETS SVN only the projects you are interested in. I played a bit with it, and modified it to generate the dependency graphs. I quickly found out that I actually like this tool much more than setuptools, even though it was pretty much using the same concepts. It took me a while to understand what I like about the tool. It is that it uses a map file to gather all the package and dependency information. As a result, it has the equivalent of a dependency graph. This makes it possible to do the operations I am interested in, eg listing all the packages required for installing a given project without actually downloading them.

The reason this is possible is that with the ETS we are not dealing with an open set of packages, like PyPI, in which packages can come and go, and no consistency is enforced. We are dealing with one suite of multiple projects that are made to work with each other. The base entity is thus a project set, on which we can make a “project map”.

What Dave has done works fantastically for development, I would like to push it further for distribution. What we expose to the user can now be a repository, in the sens of APT: a set of packages with consistent inter-dependencies, and a way of retrieving easily this information. The difference between the two, and the implications of the difference, is not something I had clearly in my mind in the beginning, but it is becoming clearer that having a repository with a project map gives a lot of added value for distributing. I’ll see if I can reuse Dave’s work to build such a tool, but do not hold your breath, I am not willingly in the business of packaging, and will probably not spend enough time on this to make it a good tool.