Hurray! The pivot article that marks my transition from physics to statistic modeling is finally out:

How to estimate the differential acceleration in a two-species atom interferometer to test the equivalence principle G Varoquaux, R A Nyman, R Geiger, P Cheinet, A Landragin and P Bouyer

To put things in context, at the end of my PhD, we had been building an atom interferometer to test the Einstein equivalence principle and my reflections on the limits of atom interferometry shifted from worrying about the underlying physics, to worrying about the estimation: the inverse problem of going from the experimental signal, to the underlying quantities that we are measuring, confounded by all the horrible experimental noise.

Atoms, light, gravity fields and free-fall planes

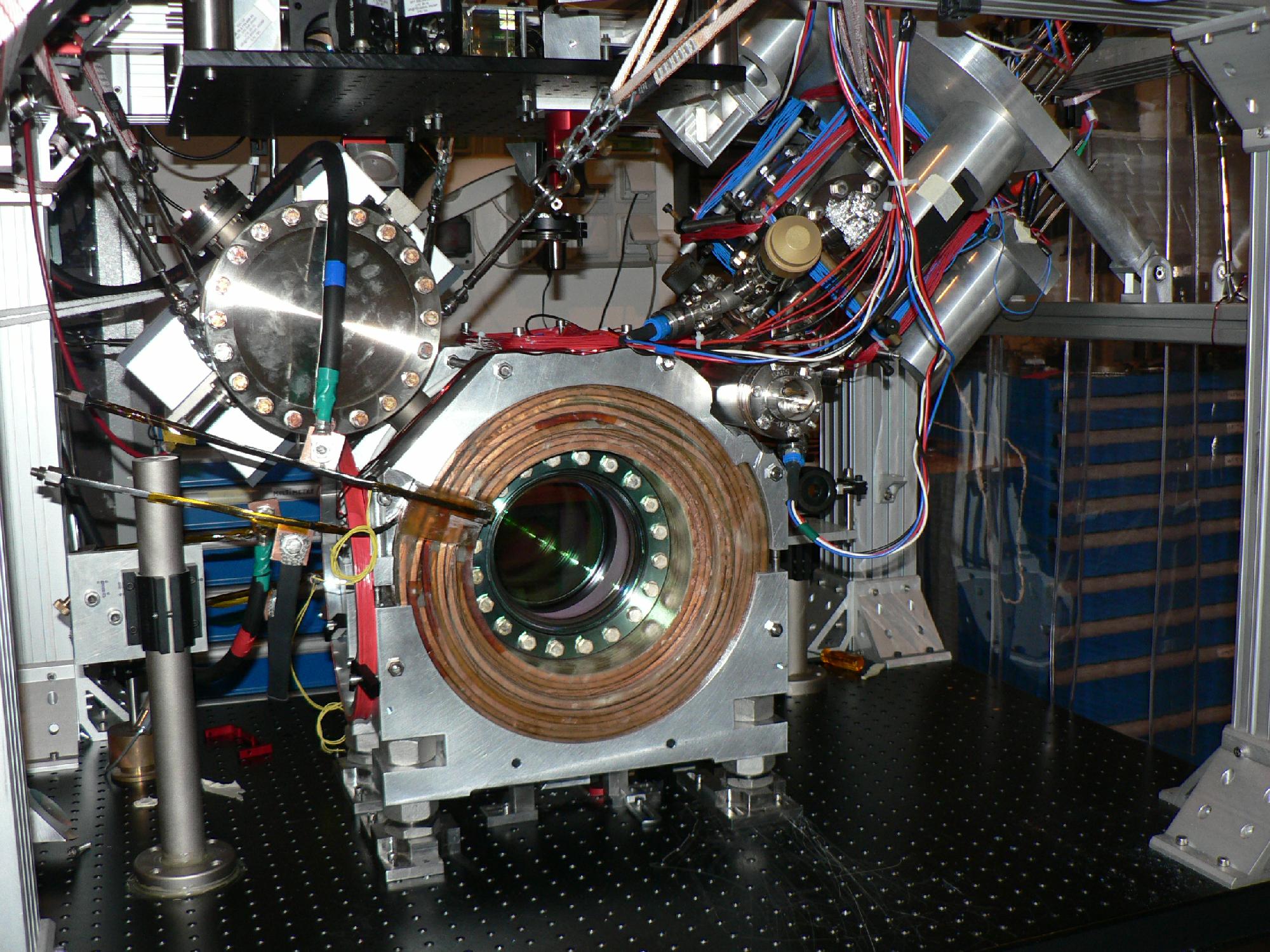

The problem is: we want to do high precision metrologic tests in a free-falling plane. We use interferometry to measure gravity fields. But rather than doing interferometry with light, we use atoms, that are much more coupled to gravity. When probing gravity fields with light, the trick is to use huge highly-sensitive interferometers. For instance the ligo and virgo projects are kilometer-long light interferometers listening for gravitational waves, and the giant ring lasers can test for tiny modifications in the Earth rotation and gravity field. Gravimetric coupling with matter waves and light waves describes the very exact same underlying physics. However, matter waves, atoms in the case of PhD, fall in gravity fields. While this is the expression of the very exact phenomena we are trying to measure, it also means that to build a very large atom interferometer, you have to let the atoms fall for a large distance. And I can attest that even laboratory-sized versions of atom-interferometric experiments are fairly nasty to run:

This is why we simply decided to build an experiment in a freely-falling plane: let’s fall with the atoms for 6 kilometers (30 seconds).

Measuring free fall, while in free fall?

Of course, the plane is not really in free fall. The pilots try as hard as possible to compensate for drag and atmospheric turbulence but there is a limit to what they can achieve with an Airbus. The atoms are a vacuum apparatus, so they are indeed in free fall (before they crash in the side of the apparatus). However, making sens of measure of fall-free made relative to an unstable, and unpredictable platform is not trivial. This is where the statistical modeling kicked in. After reading a bit about noise in interferometers, I realized that we had a well-known problem in statistics: estimation of hidden variables from noisy observations. I learned about recursive Bayesian estimation, coded a proof-of-principle algorithm for our problem (in Python, of course), and was sold. The rest of the story is about noise simulations, and trying to convince a metrology community that you could perform good measurements in a noisy environment.

It took us a lot of time (2 years) to write an article that was acceptable to the target scientific community, while keeping the core estimation and statistics message. Publishing new ideas is hard, because you are not answering questions that people already have in mind. This is why the fact that this article is out is a huge deal for me. It marks a turning point in my reflection: I switched from worrying only about forward models, with which try to describe as well as possible the system at hand, to inverse problems, in which you worry about estimating the parameters from the data.

I was startled to see that people are ready to spend a huge amount of money and efforts in improving complicated experiments involving quantum physics and very sophisticated technology, but can be weary of processing the output signal to increase statistical power. Scientific communities have their own goals that they pitch (e.g. reducing the phase noise in lasers) and there can be huge divides between different scientific interests. Realizing this played an important role in my career shift. I wanted to know more about the power of statistical modeling and machine learning applied to real-life system. I decided that to learn more, I had to work with people that had a different culture from mine. It’s been a huge amount of fun so far… More about that later.